Emulsions

It is impossible to mix oil and water. On the face of it, it almost seems peculiar that anyone should want to take an interest beyond that. There are any number of occasions when mixing oil and water is clearly unnecessary (in the fuel tank of a car), or even dangerous (chip pan fires should never be put out with water). However, a few minutes’ worth of Googling suggests that there are at least as many reasons why it is useful to mix oil and water. Mayonnaise, paint, milk and even the humble pork pie would all be quite impossible without the principle of being able to combine water and oil; without emulsions.

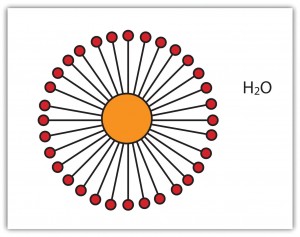

A droplet of fat (orange) surrounded by emulsifying amphiphiles. Photo copyright: flatworldknowledge.com.

The hidden ingredient in mayonnaise is the vinegar; most people know that it contains oil and egg, and sometimes even mustard powder, but watery vinegar is guessed less often. The inclusion of both oil and vinegar is the main underlying physicochemical problem with this food: to make it, you need to mix oil and water into a homogenous fluid. This requires a third agent: an emulsifier. In this case the egg yolk and mustard powder are the emulsifiers. All that is required is that the oil, vinegar, egg and mustard are mixed together in the correct proportions, and a mayonnaise is formed. The egg’s yolk contains a variety of lipids that are capable of encapsulating globules of fat that can then be suspended in the mixture of water and vinegar.

Emulsions used in paint are a bit more complicated, requiring several ingredients to work properly. They are also quite different to other types of paint, such as oil-based or acrylics). Emulsion paint relies upon particles that are dissolved in a medium containing water and another, minor, solvent. It is these solvents that evaporate when the paint dries, during which the particles polymerise to form the skin we know of as dry paint. The emulsion has been used as a sort of vehicle, to deliver the material we wish to use to create an opaque, coloured film on a surface. However, the emulsion is not completely lost, as not all of the water leaves the mixture. The layer is still capable of taking on further water in more humid conditions (e.g., in a bathroom), meaning the film cast on the surface is susceptible to water damage. Paints that are suitable for more humid environments include masonry and enamel paints, that are based on oily systems that are designed to provide a waterproof seal for a given surface.

Milk is a relatively simple and dilute emulsion, containing a mixture of fat, protein and water. In this case, trace amounts of lipids, and milk proteins, are used to encapsulate the triglycerides (fat) that can then be suspended in the water. It is therefore similar to mayonnaise in that amphiphilic species are used to create droplets that are then suspended in water. However, milk uses amphiphilic proteins as well as lipids, whereas mayonnaise does not rely upon such proteins.

That just leaves us with the delicate matter of the pork pie. This is really a fudge in terms of the basic principle of an emulsion, or rather, two fudges. Firstly, the meaty part in the middle relies upon an emulsion so that the pork fat in it does not form unattractive blobs. Secondly, the pastry relies upon a sort of emulsion in order to form an homogenous mixture. The pastry requires the use of fat, partly because it was a useful source of energy in days gone by, but also so the pastry was edible. The pastry made without fat in the middle ages was rather like stiff cardboard. This was fine for keeping bugs and rodents off the meat, but was expensive and wasteful of flour. This led to the accidental use of an emulsion for creating the pastry that holds it all together. This is not uncommon in baking, batters and pastes are emulsions, nice and runny. Doughs are emulsions as well, but with fibrous protein in them. If you fancy making an emulsion yourself, you might like to try one of James’ recipes from the final of the Great British Bake Off, for a Chiffon cake of a Union Jack (pp21).